- 0 Καλάθι Αγορών

-

ΤΟ ΚΑΛΑΘΙ ΑΓΟΡΩΝ ΣΑΣ ΕΙΝΑΙ ΑΔΕΙΟ

-

Ypsilon PST-100 Mk.II line preamplifier - Stereophile

Ypsilon PST-100 Mk.II line preamplifier

That may sound like fan hyperbole, but it's what I immediately heard a few years ago, when I first encountered Ypsilon gear at a hi-fi show. Though the company was then new to me, nothing I've heard since, at shows or at home, has deviated from that very first impression.

Ypsilon models look beautiful, even dramatically so, in their cases of thick, milled aluminum, and perhaps that's what first drew to them the reviewers and civilians who attend audio shows. What kept them there was the sound, or the lack thereof.

Many listeners tempered their initial enthusiasm with caution: A sound that good must be based on sonic tricks that only time will reveal. I found myself almost wishing that to be true, given what Ypsilon products cost. But having spent a great deal of time with Ypsilon's VPS-100 phono preamplifier ($26,000; I reviewed it in "Analog Corner" in August 2009 and March 2011), I'm convinced there are no tricks.

As is often the case in high-performance audio, less artifice comes at a high price. Ypsilon's products are very expensive, and deceptively simple in design. The PST-100 Mk.II will set you back $37,000. If you don't need the active stage, the completely passive PST-100 TA can be had for $26,000. (The active tubed stage can be retrofitted at the factory.) But either way, and considering that a preamplifier's basic job is to switch and route low-level audio signals without adding to or subtracting from any signal fed to it, these are high prices to pay for what is, essentially, nothing.

Of course, there's more to a preamp's job: It must also provide signal attenuation and, usually, gain, as well as an output impedance low enough to drive cables and interface with a power amplifier of high input impedance.

A Purist Approach

Over the past year or so, a few impressively neutral, dynamic, quiet, wide-bandwidth tube preamplifiers have passed through my listening room that rival the quiet and tonal neutrality of my reference, the solid-state darTZeel NHB-18NS. The best solid-state and tubed preamps these days are more sonically alike than different, though of course the subtle differences are the basis on which listeners who can afford such products choose.

Ypsilon's co-owner and chief designer, electrical engineer Demetris Backlavas, believes that the key to a preamplifier's sound is the means by which it attenuates the signal it's fed. Instead of the more commonly used resistor attenuation, Backlavas uses what he says is a very linear, 31-tap transformer that Ypsilon winds in-house. By comparison, he says, attenuators that use even the finest-quality resistors tend to sound grainy and discontinuous because the in-series resistor converts voltage into current, while the parallel resistor turns current back into voltage.

Not that Backlavas and his partner, Andy Hassapis, didn't try to build a better resistor-type attenuator, using a variety of materials. The problem, according to Backlavas, is that, in order to resist, a resistor must be made from a bad conductor of electricity. Copper and silver are good conductors and small-value resistors can be made from these metals that, not surprisingly, can sound very good. Unfortunately, it's impossible to use copper and silver to make high-value, wideband resistors because of the parasitic inductance that goes along with the need to use coils of very many turns. In addition, resistor-based attenuators waste signal energy by turning the attenuated energy into heat.

Nonetheless, Backlavas admits that attenuators of reasonably high quality can be built using carefully chosen resistors. You're probably listening to such a device as you read this. And, as anyone who has spent time listening to transformers (and Backlavas has spent more time listening to them than most) knows, even those with identical specs can sound remarkably different from each other, and some can ring unpleasantly or sound bad for a variety of reasons.

In fact, transformer-attenuated preamplifiers—or, more precisely in this case, autoformer-attenuated preamps, in which the primary and multi-tap secondary overlap—aren't new. Hobbyists have advocated and built them over the years, but few are commercially available. The advantage of such an attenuator over one that uses resistors is that energy is transformed and not lost as heat. Backlavas gave an example: starting with a source impedance of 1200 ohms, attenuating the signal 10dB (or 3.16 times), produces an output with lower voltage and higher current and an impedance of 120 ohms (1200/3.162), which has an easier time driving loads, unlike the less amplifier-friendly results produced by a passive-resistor attenuator.

That said, of course, transformer attenuators have their own problems that must be solved before they can produce good sound. The core material must have low hysteresis (hysteresis being like unwanted "magnetic memory") at both low and high frequencies, and linear magnetic permeability with flux and frequency. c

So, in audio as in life, execution is as important as design—and the PST-100 Mk.II is, per Backlavas, a "fairly simple design."

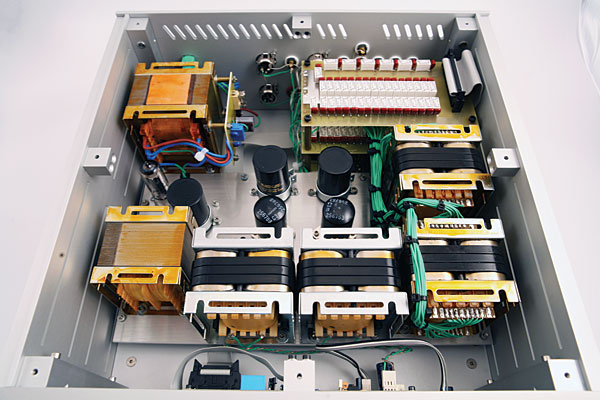

The volume control output transformer, "painstakingly designed and optimized," is custom-wound at Ypsilon on an amorphous double-C core, itself chosen via listening tests. The impedance of the output stage, which is hardwired with fine, custom-drawn silver wire, is around 600 ohms. The active stage is essentially a small, single-ended amplifier.

However, there is more to know about this microprocessor-controlled circuit, which features both active and passive modes of operation. In active mode, high-quality silver-contact relays route the input directly to the transformer volume control, up to step 6. The controller then routes steps 7–37 through the active stage, to produce a maximum gain of 17dB.

When the PST-100 is set to passive mode, its active stage never kicks in. (The PST-100 is available in a less-expensive TA version that only operates in passive mode.) Instead, the signal is routed only to the transformer volume attenuator, bypassing the active stage altogether, with step 31 producing 0dB (unity) gain. In order to drive the transformer efficiently, the manual suggests not running the system in passive mode with sources whose output impedance exceeds 3k ohms.

Regardless of mode, attenuation is 3dB per step up to step 5. Between steps 5 and 10, each step is 2dB, and steps 10–28 are 1.5dB each. The final three steps (35–37) offer 1dB of attenuation each.

In addition to transformer-based attenuation, the PST-100 features 6CA4 tube rectification, choke supply filtering, and a zero-feedback active stage based on a carefully selected Siemens C3m pentode tube configured as a true triode and transformer-coupled to the output. The power supply uses Mundorf and Jensen four-pole electrolytic caps, chosen based on listening tests.

Designer Demetris Backlavas told me that, other than the silver-plated relays and transformer, the only components in the PST-100's signal path in active mode are a resistor bypassed with a Silmic2 capacitor in the cathode, and a grid stopper resistor—and, of course, the C3m tube. He also told me that he'd kept control circuitry to an "absolute minimum" in order to avoid high-frequency noise, and that, to avoid introducing noise, control signals within the preamp are static and not clocked.

No knobs, no switches

The PST-100 Mk.II's chassis, milled from thick panels of satin-finished aluminum, has no switches or knobs. The remote control handles all functions—don't misplace it. Fortunately, it, too, is milled from a hefty chunk of aluminum. If you sit on it, you'll know it—and if you don't, you'd better get to the gym.

On turn-on, an LCD screen on the front panel lights up, and for 30 seconds identifies the unit as the "Ypsilon PST-100 Mk.II," after which it changes to "Volume 00, Input 1 CD." At that point, or whenever you set the volume to "00," you can use the remote's topmost button, labeled "S," to toggle between the PST-100's active and passive modes; your selection is indicated on the display. At any volume level other than "00," this button acts as a Mute control. The next button down extinguishes the rather bright screen, while the center two buttons control volume, and the lower pair handle source selection. The inputs are preprogrammed with identifying labels (CD, Phono, Cinema, etc.) that can't be changed.

On the rear panel are six pairs of chassis-mounted inputs, five of them RCA jacks. Input 6 is unbalanced XLR. Next to the inputs are RCA and unbalanced XLR outputs. A pair of Tape Out RCA jacks is located above Input 4's RCA jacks. As on the VPS-100 phono preamp, the PST-100 Mk.II's On/Off switch is on the rear panel—less than optimally convenient, but not a real problem.

Sublime nonsound

If the Ypsilon phono preamp is any indication, the PST-100 Mk.II requires a very long break-in period. There's a lot of wire in those transformers. Even after the PST-100 had spent a few months in my system, I still wasn't sure it had fully broken in by the time I had to write this review. But even raw out of the box, the PST-100 Mk.II produced that Ypsilon "nonsound" heard at audio shows throughout the world. Still, the sound continued to open up and become more dynamic as time passed, but with little change in its tonal balance or transient performance.

While I listened in both active and passive modes, the latter's output, even with the attenuator well down from its 0dB maximum level, was more than enough to drive my Musical Fidelity Titan amp and my relatively sensitive Wilson Audio MAXX 3 speakers In passive mode, there was literally nothing but the silver relay and the step-down transformer between the incoming signal and the interconnect to the power amplifier. The PST-100 sounded about as close to the source as can be imagined. All sources, analog or digital, were steps more transparent, three-dimensional, and closer to sounding "live"—or at least closer to the source going directly to the amplifier—than I've otherwise heard in my listening room.

One of the last records I played before switching from the darTZeel to the Ypsilon was a 45rpm, single-sided, four-LP reissue of Jascha Heifetz's recording of Bruch's Scottish Fantasy and Vieuxtemp's Violin Concerto 5, with Sir Malcolm Sargent conducting the New Symphony Orchestra of London (RCA Living Stereo/Classic LSC-2603-45-200G). While it's considered to be one of RCA's best Living Stereo recordings, it's licensed from the UK and was originally produced by Decca—the engineer was the great Kenneth Wilkinson. The recording of Heifetz's violin is particularly exquisite, and a good test of a preamp's ability to convey instrumental attack, textures, and harmonic structures, not to mention precise imaging and dimensionality.

The PST-100 Mk.II managed all of those things with a purity, delicacy, and verisimilitude that surpassed the performance of any preamplifier I've heard—and I've heard and owned some very good ones. When Heifetz plays spiccato (light, staccato bowing), each time his bow bounced off a string, the Ypsilon reproduced the character of that physical contact—its texture and tonality—with glistening transparency and physical dimensionality. The only word appropriate to describe my first hearing of this album through the PST-100 Mk.II is thrilling. This familiar recording sounded more "real" than I'd ever heard it, with Heifetz more clearly delineated in space in front, and the orchestra arrayed behind him.

Against the darTZeel

After the PST-100 Mk.II had been installed, two EMI Classics recordings arrived, in a recent reissue by Esoteric Remasters (SACD/CD ESSE-90048): Otto Klemperer and the New Philharmonia Orchestra performing Franck's Symphony in D, at Abbey Road Studios in 1966 (originally EMI 5276); and Schumann's Symphony 4, recorded at the famed Kingsway Hall in 1960 (EMI 2398). I was familiar with these works, though not these recordings of them, but after numerous plays I had a pretty good handle on their sounds. The Kingsway recording was more spacious, and done from a mid-hall perspective, but both are very fine "vintage" symphonic recordings, and the 2010 transfer from analog tape to DSD, made at the JVC Mastering Center, was pristine.

Through the Ypsilon in passive mode, particularly the Schumann sounded moderately three-dimensional, with a wide stage perspective that was somewhat out of character for what, given the mid-hall balance. The same recording through the darTZeel NHB-108NS produced a fine but less transparent sound that was tonally cooler but equally spacious and precise. The strings were somewhat drier and the perspective slightly flatter, but the resolution of detail, particularly low-level information, was equally good. The stage width was identical, as were the dynamics. The biggest differences were in terms of harmonics and transparency: The Ypsilon produced more vivid colors, as well as a level of transparency and purity I'd never before experienced in my system.

I don't mean to exaggerate these differences—the sonic distance between the darTZeel and the Ypsilon wasn't enormous. Once my ears had settled in with either of these artifact-free sounds, I was always musically satisfied. But when I went back to the recording of Bruch's Scottish Fantasy, the Ypsilon reproduced Heifetz's silky tone and shimmering vibrato with greater physicality, and an intensity of texture and harmonic completeness that made his violin sound more lifelike.

In fact, there was no downside to the Ypsilon's sound with any genre of music. While in the UK recently, I picked up an original German pressing of Pat Metheny and Lyle Mays' intensely atmospheric As Falls Wichita, So Falls Wichita Falls (LP, ECM 1190). (A few weeks later I found myself in Wichita, on my way to Salina, Kansas, to visit Quality Record Pressing, Chad Kassem's new vinyl pressing plant—see this month's "Analog Corner.") Through the Ypsilon, the deep-bass strokes near the beginning of the title track, and the ensuing deep synth drones and richly recorded drum wallops, were reproduced with visceral intensity and their familiar full extension, while the shimmering bell trees produced fast transient shivers, and individual percussion notes rang with pristine clarity and no unnatural etch. Transformers can ring and produce a hazy aftertaste, in my experience, but the PST-100 Mk.II produced no such artifact.

And when "As Falls Wichita . . ." explodes about three-fourths of the way through its nearly 21 minutes, the Ypsilon did not restrain that macrodynamic thrust—there was nothing polite about this preamp's performance. But when called on to produce great delicacy, it did that as well. Active electronic stages often trade a modicum of transparency for a worthwhile increase in musical grip. In its passive mode, the PST-100 seemed to produce unprecedented transparency while exhibiting complete control and speed. Rhythm'n'pace were as honest and natural as the recording allowed.

Through the darTZeel NHB-18NS, the well-recorded Metheny-Mays LP sounded equally dynamic and wideband, but was slightly less transparent and spacious, less harmonically full-bodied, and sounded a bit grayed-out by comparison. Was that because the darTZeel doesn't pass along colors, or because the passive Ypsilon was adding them? I have no idea.

Going Active

Switching to active mode and raising the volume above the switchover point after the first six control steps to ascertain the sound of the Ypsilon's tube amplification section meant playing music loud, but I'm okay with that. (I used an SPL meter to match the levels, and never let the volume go above 95dB.)

Not surprisingly, the PST-100 in active mode sounded similar to the VPS-100 phono preamplifier. While the PST uses a different Siemens tube, the two components are more similar than different in design—and, of course, their transformers use similar technology, and are wound at the Ypsilon factory by the same team.

There was remarkably little difference between the PST-100's active and passive stages. I wouldn't want to be forced into a double-blind test here, but the active stage was just slightly darker, and more liquid or soft. Noise was nonexistent in passive mode, inaudible in active.

Going from the very fine solid-state darTZeel to the tubed Ypsilon and, months later, back again to the darTZeel, produced no surprises and only minor disappointment. Each is a world-class preamplifier: quiet, transparent, dynamic, and with a pure sound. Both handled the incoming signal precisely. They were more alike than different, but every difference favored the Ypsilon.

The Ypsilon's performance was equally good with rock, techno, jazz, and every other genre. XX, the Mercury Award–winning debut album by The XX (LP, XL LP450), aside from being very well recorded overall, contains some of the deepest notes I've ever heard from a record. The Ypsilon passed them along as well as the darTZeel does, with full extension and intensity. It also presented equally well everything else on XX, but with that bit of added transparency and clarity already noted.

If there was any downside to the Ypsilon PST-100 Mk.II in active mode, I didn't hear it—whatever faults JA's measurements might show were inaudible. Ypsilon specifies no signal/noise or harmonic-distortion specs for the PST-100 Mk.II, but based purely on what I heard, the preamp was essentially free of noise in passive mode, and equally quiet in active mode. In passive mode, if output-impedance variations reached the point where frequency rolloff occurred, I didn't hear it. In either mode, music erupted from jet-black backgrounds. If the measurements show any nonlinearities, they surely must be minor; the Ypsilon was as airy and extended and spacious on top, and as tight-fisted and extended on the bottom, as any preamplifier I've heard.

Conclusions

Ypsilon's PST-100 Mk.II is a full-function preamplifier that can drive most amplifiers in its passive mode, but can add a remarkably transparent, tube-based active stage when needed. It is beautifully and simply built using custom-designed transformers wound in-house, point-to-point wiring with custom-drawn silver wire, and hand-selected tubes designed for long, quiet, trouble-free use.

The PST-100 Mk.II is, as designer Demetris Backlavas modestly claims, "a fairly simple design." Simplicity can have definite benefits and equally definite costs—yet despite its minimalism, the PST-100 has no sonic or functional disadvantages that I could hear or experience. It seemed to add nothing to and subtract nothing from any signal it was fed. It didn't add noise or etch or edge, nor did it subtract transient clarity, dynamic slam, or frequency extremes. What it sounded like in active mode was the mythical straight wire with gain.

The preamp's six inputs should be enough for most audio enthusiasts, and its Tape Out is a useful addition for recording to any format. In the interests of sonic purity and circuit simplicity, the PST-100 Mk.II lacks a Mono switch or a Balance control—but if you're interested in maximizing transparency and accurate-to-the-source pass-through with attenuation and no resistors in the signal path, the Ypsilon PST-100 Mk.II is the best preamplifier I have ever heard.

At $37,000, the PST-100 Mk.II is very expensive; but given how it's made and how it sounds, and assuming you can afford it, it's well worth the money. For now, the Ypsilon PST-100 Mk.II is the most transparent and, therefore, the most perfect audio component I have ever heard—or not heard.

Description: Tubed preamplifier with remote control, transformer-operated volume control, and switchable passive mode. Tube complement: 6CA4, C3m. Inputs: 5 unbalanced line-level (RCA), 1 unbalanced (XLR). Outputs: 1 unbalanced (RCA), 1 unbalanced (XLR), 1 buffered Tape Out (RCA). Frequency response: 9Hz–100kHz, –3dB. THD: not specified. Signal/noise: not specified. Channel separation: not specified. Maximum output: not specified. Input impedance: 50k ohms. Output impedance: 150 ohms.

Dimensions: 15.6" (400mm) W by 7" (180mm) H by 16" (410mm) D. Weight: 55 lbs (25kg).

Serial Number Of Unit Reviewed: 017.

Prices: $37,000; completely passive PST-100 TA, $26,000. Approximate number of dealers: 8.

Manufacturer: Ypsilon Electronics, Y8 AG. Athanasioy Street, Peania 19002, Athens, Greece. Tel: (30) 210-66-44-588. Fax: (30) 210-66-44-812. Web: www.ypsilonelectronics.com

Σεβόμαστε την ιδιωτικότητά σας

Τα απαραίτητα για τη λειτουργία του ιστοτόπου cookies είναι πάντα ενεργά, ενώ μπορείτε να αλλάξετε τις ρυθμίσεις για τα cookies που αφορούν στη συλλογή στατιστικών ή marketing.